The complexity of the snakebite crisis in India became clear when my phone rang

I started off as an excited kid with lots of questions about snakes, while trying to understand why people kill them on sight. As I grew up, oblivious about the pain and suffering, the internet first arrived in the villages of West Bengal around 1998. Of course, frustratingly slow. As I started reading the occasional online article, I slowly started grasping the reality that people die due to snakebite. This made me think. Every day I would spend a few hours surveying online literature related to snakebite in India. I came across many and that made my job as a conservationist more difficult, sometimes so much that it felt hopeless. It was clear that if I could not provide prevention and remedy for snakebite, I couldn’t talk about snake conservation, at least in India.

It was only when I ventured out, forming an organization that was on call around the clock, providing snake rescue and snakebite SOS for five blocks within the Hooghly district, covering an area of about 840 square kilometers, did I realize the scale of the conflict and the complexity of the problem.

Eight year old boy who died due to a Naja naja bite eight hours later without any treatment.

The decisive day of my life came when I received a phone call about a snakebite SOS, and rushed to the spot to evacuate the victim who was an eight year old boy. He had been bitten by a sub-adult Naja naja while playing inside the house. I reached their house to be told that the boy had been taken to a faith healer after the bite, and then to another faith healer. It took eight hours for that child to die while the nearest source of antivenom was twenty minutes from their house. As I looked at the lifeless body of that kid that day, who had been alive and playing a few hours ago, I asked a few questions to myself – Whose fault was it? The parents? The Child? The faith healers? Or the system that exists? I am still looking for that answer.

When the complexities of the snakebite problem was unfolding in front of me, I had been going into the communities through our rescue networks and snakebite education camps. I realized this problem had been neglected beyond imagination. It was not the end.

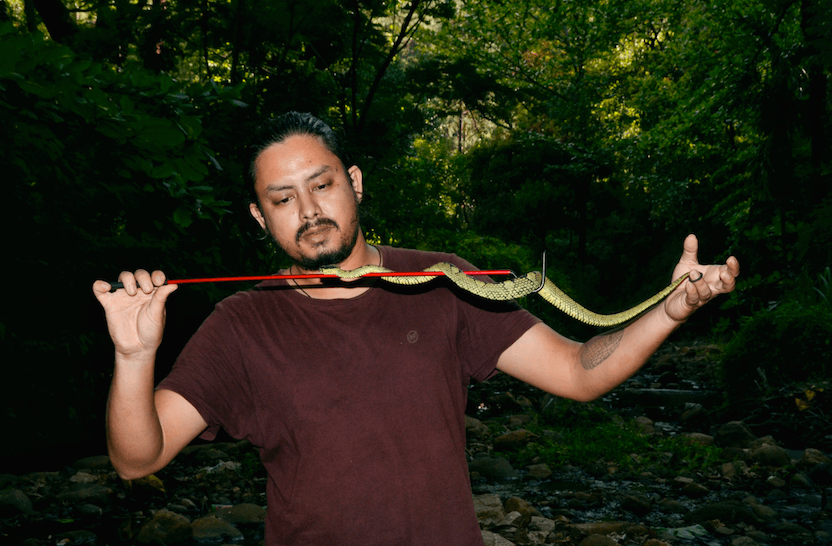

Vishal with Naja oxiana which was sampled for venom and dna for the first time ever from India.

As the snakebite calls grew and I took patients to rural hospitals, I realized how helpless a lot of our clinicians were. Those clinicians were also victims of the negligence that the issue of snakebite has been suffering. I came to know that the MBBS course in West Bengal does not have a standard or even a specific course or training in the curriculum that deals with snakebite. All that these clinicians get is a little exposure to snakebite treatment and management when they are posted as house staff or doing their internship at a tertiary care hospital or a medical college. This was complicated and sobering enough, but soon I was bombarded by the questions of antivenom efficacy, venom variability, composition, and medically significant species outside the “Big Four”.

Vishal with a Trimeresurus trigonocephalus in Sri Lanka. He worked with the University of Peradeniya in setting up a herpetarium for the production of Sri Lankan venoms for the design and manufacture of a SL spec.

I never had the time or will amidst the chaos snakebite offers, to even fathom anything else apart from learning more about the human-snake conflict and about the snakes responsible for the bites leading to the pain and suffering. It took my colleagues and myself more than 15 years of voluntary involvement in establishing an organization that deals with conservation, conflict mitigation, research, and community engagement. It still isn’t enough. I have been successful in developing important collaborations, planned projects, spent days and nights finding snakes to be studied, had sleepless nights at hospitals waiting for good news about snakebite patients, and provided voluntary services to many individuals, organizations and institutes. After running helter-skelter, trying to find solutions, today I have a better understanding of the problem and am currently leading multiple snakebite projects in different parts of the country, sampling snakes of medical importance for the first time in history from various regions, engaging with kids and adults, working on snakebite education films and adopting villages and making them snakebite death free for the last 10 years, despite of venomous snakebites. I know I am on the right track.

I don’t want to see those kids suffocate in front of their dreams or limp away with one leg from their playgrounds. I don’t want to look at that father’s blank face holding his dead eight year old boy, unable to speak, unable to think. I believe that with a little bit of luck and a lot of hard work and support from organizations and leaders of the world we can reduce the pain and suffering caused by snakebite.