What Mkhulu taught me

Mkhulu was sitting on his grass mat in his traditional mud and stick home, when a Mozambique spitting cobra slithered through a gap in the wall. It came from behind the old man, and when he moved his foot, the snake bit him.

I received a frantic call for antivenom from the hospital as they didn’t have stock. Within two hours, Mkhulu received the desperately needed treatment.

He responded well, and despite the pain, was cheerful and laughed at all of us fussing around him. As I sat with him, he told me endless stories about snakes that he had learnt from his elders, his beliefs on how to keep them away, and how his children had convinced him not to use a traditional treatment but to go to hospital. Apparently they had been to the community outreach program hosted by the Eswatini Antivenom Foundation, and knew the importance of getting to a medical facility without delay.

The first few days looked promising. As always happens with bites from the Mozambique spitting cobra, there is always necrosis, no matter how much antivenom we administer. But the necrotic area was contained, the swelling had stopped and we were confident that Mkhulu would soon be able to go home.

It was not to be.

Because of his diabetes, the wound would just not heal. By now, we were good friends. We both looked forward to the visits and long chats. As a subsistence farmer, having two legs was essential. Although in his 80’s, Mkhulu was fit and strong. His garden, chickens and goats were his wealth, and food security.

After several weeks, we received the devastating news that the only option was to amputate his leg below the knee. He held my hand tightly and with tears running down his ancient face, begged me; “fix it, please fix it, don’t let them take my leg”.

But we were out of options. If we didn’t remove the leg, he could lose his life.

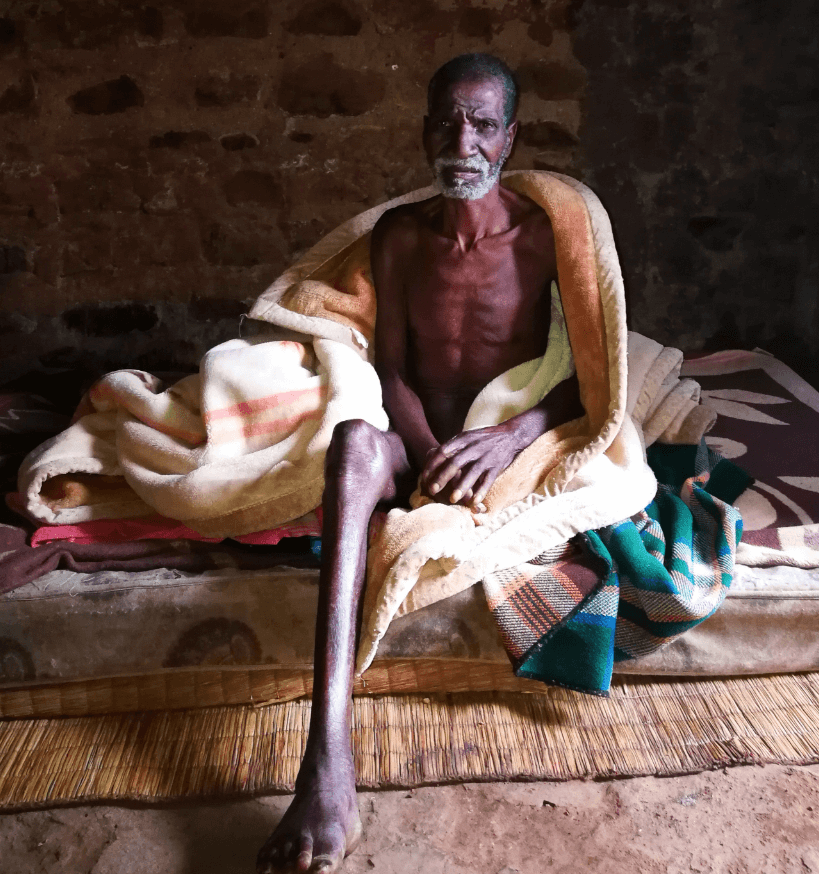

When he was finally discharged from the hospital, he had lost so much weight and because of the extended hospital stay, had lost all his muscle mass. He was so weak, he couldn’t even use crutches.

My first home-visit was heart-breaking. He was sitting on his grass mat, with a blanket around his shoulders, thin as a reed and full of bedsores. His beautiful garden was dry – not a single vegetable had survived. His livestock was gone too, his stepson had sold them. Because he couldn’t use his crutches, he couldn’t go to the bathroom. He had nothing to eat except for a thin porridge.

The priority was adult diapers, and food. Followed by a wheelchair and because he didn’t have the strength anymore to pull himself up onto the chair, we got him a bed. The first bed he had ever slept in. He could shuffle from the bed onto his chair and wheel himself outside.

Mkhulu in his first-ever bed after suffering a snakebite and the amputation that followed.

I learnt a great deal from Mkhulu. As a subsistence farmer, when he lost his leg, he lost everything. From being a proud leader of his little homestead, he became a pauper, begging for help and hand-outs. Snakebite isn’t just the treatment of the bite – we need to understand that lives are changed forever, the effects last a lifetime. The mental burden is as significant as the physical.

Mkhulu lived for another year, before passing peacefully in his new bed. His dignity restored.

Thea Litschka-Koen in the founder of Eswatini Antivenom Foundation in Eswatini.

This blog was written as part of the Women Champions of Snakebite campaign, supported by the Lillian Lincoln Foundation, Health Action International and Global Snakebite Initiative.

This blog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Licence. View a copy of this licence at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/